“If you want to debate me, first define terms.”

This succinct advice highlights a critical issue in the blockchain industry: the debate around decentralisation is often muddled because people aren’t talking about the same thing. The term ‘decentralisation’ is thrown around liberally, yet it’s become a contentious buzzword that loses meaning without a shared definition. Decentralisation is hailed as the cornerstone of blockchain technology, promising security, transparency, and democratic governance. However, the wide array of interpretations complicates discussions, leading to confusion and miscommunication. This article aims to provide clarity by focusing specifically on structural decentralisation within blockchain technology, examining its implications, and exploring how it influences the design and resilience of networks like Bitcoin. By delving into the architectural and operational specifics of structural decentralisation, we hope to foster more informed and productive debates on the technological and strategic future of blockchain systems.

Structural decentralisation

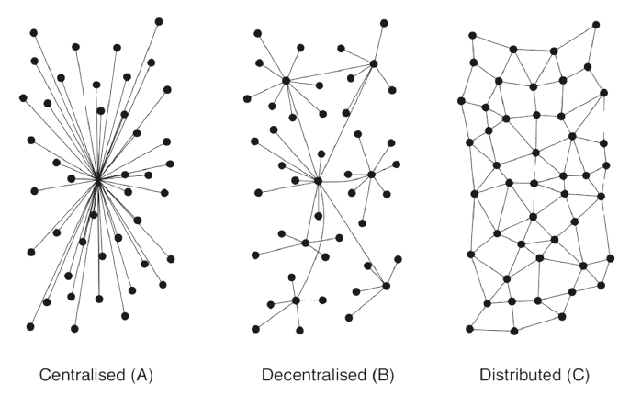

Structural decentralisation, as conceptualised by Paul Baran, refers to the architecture of a network that is designed to avoid single points of failure, thereby enhancing its resilience and robustness. In his seminal work on distributed communications, Baran (1964) introduced the idea of a network that could sustain operation even if parts of it were destroyed or incapacitated. This contrasted with centralised networks, where a single point of failure could bring down the entire system, and decentralised networks, which, while more resilient than centralised ones, still relied on several key nodes that, if compromised, could significantly impact the network’s functionality. Baran’s vision was for a distributed network, a structure with no central point of failure and with paths that could dynamically reroute around damaged or destroyed nodes.

Mandala Networks and their efficiency

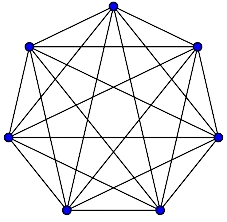

Mandala (or Small World) networks, characterised by their high degree of interconnectivity and short path lengths between any two nodes, embody the essence of Baran’s decentralised networks. These networks manage to combine the efficiency found in centralised systems — through their highly connected centres — with the resilience and robustness of distributed systems. In a Mandala network, most nodes can be reached from each other by a small number of steps, despite the network’s large size. This structure facilitates efficient communication and data transfer across the network, mitigating some common drawbacks of distributed systems, such as increased routing complexity and latency issues.

Economic incentives in Bitcoin mining

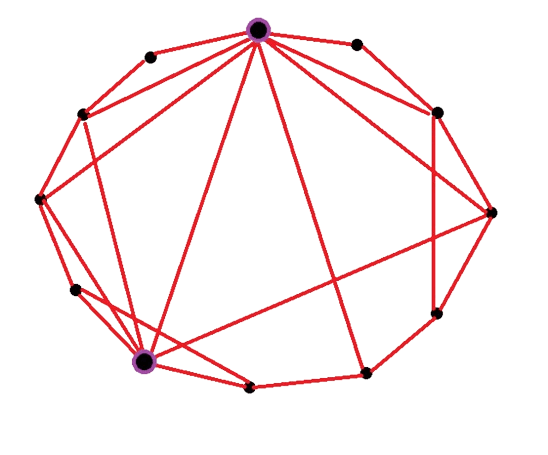

In the context of Bitcoin, the economic incentives for miners drive the formation of a Mandala network. Miners are motivated to maximise their profits by finding the most efficient connections to other miners, thereby minimising latency and the number of hops needed to propagate new transactions and blocks across the network. This optimization leads to the emergence of a highly interconnected network with attributes akin to a near-complete graph, where most miners have direct or near-direct connections to each other.

This network topology ensures that Bitcoin retains the beneficial attributes of a distributed system — particularly its resilience against attacks and failures — while also leveraging the efficiency of a centralised network in terms of communication and data transfer speed. By incentivizing miners to create optimal pathways for data to travel, Bitcoin naturally evolves into a structure that is robust against centralised control or failure, yet efficient enough to process transactions and blocks at a pace that supports its function as a global decentralised ledger.

Even with a relatively small number of miners, the inherent interconnectedness and geographical distribution of the Bitcoin network confer significant resilience. The economic drivers behind Bitcoin mining ensure that, despite the concentration of mining power, the network retains a robustness akin to a more evenly distributed system. This is because the strategic placement and high connectivity of miners across various locations globally create a mesh of redundancy and fault tolerance. Consequently, the network can withstand substantial adversities, including targeted attacks and local failures, without compromising its overall integrity and operational continuity.

Implications for structural decentralisation

The structural decentralisation of Bitcoin, as informed by the principles of Mandala networks, accomplishes several key objectives:

Resilience:

The network remains operational even if parts of it are attacked or fail, as the high degree of interconnectedness allows for the rapid rerouting of information.

Efficiency:

Despite its distributed nature, the network achieves efficiency in communication and data transfer, rivalling more centralised systems in terms of latency and speed.

Security:

The decentralised structure protects against attacks that would typically exploit central points of failure or control, thereby enhancing the overall security of the Bitcoin network.

In essence, the economic incentives within Bitcoin mining and the resulting Mandala network topology embody the principles of structural distribution outlined by Baran. This architecture not only ensures the resilience and security of the network but does so in a manner that maintains, and even enhances, its operational efficiency.

Key takeaways

In conclusion, the concept of structural decentralisation, while foundational to blockchain’s architecture and resilience, has been clouded by the varied and often conflated interpretations within the broader discourse. The term ‘decentralisation’ has evolved beyond its original technical implications, losing clarity and becoming a catch-all phrase that risks obscuring the specific mechanisms that ensure blockchain networks like Bitcoin operate securely and efficiently. Moving forward, it’s crucial to shift the focus from the broad, sometimes nebulous invocation of decentralisation to a more precise discussion of the specific architectural and economic principles that underpin the functionality and integrity of these systems. By grounding the conversation in clear, definable terms, we can better assess and advance the technology in a way that stays true to its core principles of security, transparency, and peer-to-peer interaction, without getting lost in the ambiguity that currently surrounds the concept of decentralisation.